PROBLEM SOLVING

Referred Pain - Endodontic Diagnosis

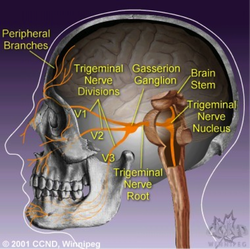

Referred pain occurs in dentistry. Many dentists have had the experience of a patient presenting and complaining of pain, pointing to a specific tooth, and ultimately being incorrect in their assessment as to where the pain originates. This is due to conversion of stimuli and summation of information in the Gasserion Ganglion and the brain stem. Any branch of the Trigeminal Nerve can be affected. The impulses pass from the site of stimulus, along the respective nerve T1 or T2 or T3, and converge in the Gasserion Ganglion. The impulses continue onto the Trigeminal Nucleus and then move along the spino-thalamic tract to the Hypothalamus and Thalamus.

The summation of information gathered in these structures often misleads the patient into thinking their problem is related to one area of the mouth whereas the affected tooth is actually in another area. This problem in endodontics occurs when the pulp of a tooth is affected but the inflammatory reaction has not passed beyond the confines of the tooth into the periodontal ligament spaces. Thus there is no sensitivity to percussion. The clinical tests of value in determining which tooth has the pulpal problem are the cold and heat tests. The problem is usually related to a state of irreversible pulpitis, or partial pulpal necrosis.

The objectives of the thermal tests are to duplicate patient discomfort or to relieve same. Cold tests will excite a vital inflamed pulp, whereas heat will illicit an untoward response when the coronal portion of the pulp has deteriorated. Cold tests may also reduce patient discomfort when partial pulpal necrosis is present.

If one is unsure as to which arch is affected, an anesthetic test can be performed to eliminate sensations from either the maxillary or mandibular branches of the Trigeminal Nerve. If one is still unsure of the site of origin after performing the thermal and anesthetic tests, it is best to re-evaluate patient symptoms another day.

If anesthetic tests do not alleviate patient discomfort, then the dentist must consider the patients’ pain is not of endodontic origin. These patients should be referred to our oral medicine colleagues for further assessment.

The summation of information gathered in these structures often misleads the patient into thinking their problem is related to one area of the mouth whereas the affected tooth is actually in another area. This problem in endodontics occurs when the pulp of a tooth is affected but the inflammatory reaction has not passed beyond the confines of the tooth into the periodontal ligament spaces. Thus there is no sensitivity to percussion. The clinical tests of value in determining which tooth has the pulpal problem are the cold and heat tests. The problem is usually related to a state of irreversible pulpitis, or partial pulpal necrosis.

The objectives of the thermal tests are to duplicate patient discomfort or to relieve same. Cold tests will excite a vital inflamed pulp, whereas heat will illicit an untoward response when the coronal portion of the pulp has deteriorated. Cold tests may also reduce patient discomfort when partial pulpal necrosis is present.

If one is unsure as to which arch is affected, an anesthetic test can be performed to eliminate sensations from either the maxillary or mandibular branches of the Trigeminal Nerve. If one is still unsure of the site of origin after performing the thermal and anesthetic tests, it is best to re-evaluate patient symptoms another day.

If anesthetic tests do not alleviate patient discomfort, then the dentist must consider the patients’ pain is not of endodontic origin. These patients should be referred to our oral medicine colleagues for further assessment.

PERFORATIONS:

Perforations occur in dentistry when dentists attempt to access root canal systems which are calcified or tortuous. They also occur when overinstrumentation is performed in any region of the root canal system.

Perforations can be treated and a good prognosis is expected if treated properly. The most important consideration is to seal the perforation immediately.

There are various materials available to effect this and depending upon the level where the perforation occurs, the dentist may decide to use different materials for different areas of the tooth. The following guidelines may be helpful.

1. Cervical region perforation - Ideally, this perforation should be sealed via an internal approach with amalgam. Composite is not the material of choice as it is porous and cannot seal as well as amalgam. If esthetics are not a consideration such as in the molar region, then amalgam is the choice material. If there is an overextension of the amalgam, then a simple gingival flap should be reflected and the amalgam carved to restore the contours of the tooth in the affected region.

2. Furcation perforation of the molars and bicuspids - MTA should be used to seal these furcation perforations ideally. This demands that treatment of the root canal spaces be aborted as it is necessary for the MTA to set and this takes approximately 4 hours. If the dentist deems it important for endodontic treatment to be continued even though the perforation has occurred, then the perforated site can be temporarily sealed with materials such as Cavit, IRM, or glass ionomer cement. This seal should allow the practitioner to prevent leakage of the irrigating solutions into periodontium in the perforated site and prevent more damage to the tissues outside the confines of the root canal system.

3. Lateral perforation of the root - There are many shapes to a perforation of the root and different areas in which the perforation can occur.

The above recommendations are directed at mechanical perforations which have been created by the operator. If there is an old long standing perforation with a lesion present, this should be treated differently than the perforation which was fresh. An example is where a post has perforated the root canal space and a lesion developed subsequently. This area is now an infected area.

Three actions must be taken to effectively treat the "old, long standing perforation" with a lesion present.

Perforations can be treated and a good prognosis is expected if treated properly. The most important consideration is to seal the perforation immediately.

There are various materials available to effect this and depending upon the level where the perforation occurs, the dentist may decide to use different materials for different areas of the tooth. The following guidelines may be helpful.

1. Cervical region perforation - Ideally, this perforation should be sealed via an internal approach with amalgam. Composite is not the material of choice as it is porous and cannot seal as well as amalgam. If esthetics are not a consideration such as in the molar region, then amalgam is the choice material. If there is an overextension of the amalgam, then a simple gingival flap should be reflected and the amalgam carved to restore the contours of the tooth in the affected region.

2. Furcation perforation of the molars and bicuspids - MTA should be used to seal these furcation perforations ideally. This demands that treatment of the root canal spaces be aborted as it is necessary for the MTA to set and this takes approximately 4 hours. If the dentist deems it important for endodontic treatment to be continued even though the perforation has occurred, then the perforated site can be temporarily sealed with materials such as Cavit, IRM, or glass ionomer cement. This seal should allow the practitioner to prevent leakage of the irrigating solutions into periodontium in the perforated site and prevent more damage to the tissues outside the confines of the root canal system.

3. Lateral perforation of the root - There are many shapes to a perforation of the root and different areas in which the perforation can occur.

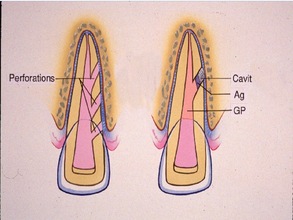

- Round Perforation in the cervical 1/3 of the root - If this can be visualized, then the seal can be effected with MTA or any glass ionomer cement. If it cannot be visualized, then it may be best to seal the perf with Cavit and allow this to set. At a second appointment, the Cavit will have hardened and the canal can be instrumented and obturated without disturbing the seal. The apical 2/3's of the canal should be obturated using gutta percha but the portion of the canal which has the perforation present, should be sealed with a cement or amalgam.

- Round Perforation in the middle 1/3 of the root - This perforation can be sealed as mentioned above. Sometimes it is possible to treat this perforation as a lateral canal and one can effect an actual "stop". If this can be performed, then the perforated site may be sealed using gutta percha and sealer.

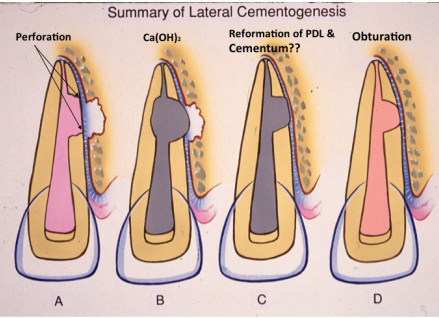

- Round Perforation in the apical 1/3 of the root - As mentioned above, this can be treated as a second canal and obturated using gutta percha and sealer. Alternatively, calcium hydroxide can be placed to effect a "stop" and the canal and perforation are then obturated. The calcium hydroxide will prevent overfilling.

- Strip Perforation of the root - This is a more serious problem as the stripping perforation is linear and more difficult to seal properly. However, the outcome of treatment may be acceptable for a few years if the perforation is sealed completely. Calcium hydroxide can be used initially to seal the perforation temporarily and arrest the bleeding which usually is encountered. Cavit can also be used to seal this type of perforation. Following the placement of the Cavit or calcium hydroxide, the practitioner should unsure the canal is patent by placing a #10 and #15 file to working length thereby creating a pathway through the material. Once the root canal is obturated, the Cavit and/or calcium hydroxide can be removed and MTA placed. However, it is not necessary to place MTA if the perforation was well sealed by the other materials. The remainder of the canal should then be sealed with a cement which will quickly set.

The above recommendations are directed at mechanical perforations which have been created by the operator. If there is an old long standing perforation with a lesion present, this should be treated differently than the perforation which was fresh. An example is where a post has perforated the root canal space and a lesion developed subsequently. This area is now an infected area.

Three actions must be taken to effectively treat the "old, long standing perforation" with a lesion present.

- Expose the perforated area -- If a post is present, it must be removed. If the root canal space is obturated with a root filling material, this must be removed to gain access to the site.

- Reduce the infection which is present - this may take a few appointments. The root canal space should be irrigated with sodium hypochlorite and this chemical shouldbe allowed to sit within the root canal for approximately 1/2 hour. Calcium hydroxide should be placed within the root canal and the patient reappointed. At a second session, irrigation of the space for at least 1/2 hour should be performed once again. Calcium hydroxide should again be employed as an interappointment medicament. Allow at least one month for healing to occur. If a sinus tract was present pre-operatively, this should have healed. If so, the perforated site can be sealed. If not, repeat the irrigation and again place calcium hydroxide. If there was no sinus tract which allows the practitioner to assess healing, then the practitioner may wish to wait for radiographic evidence of healing prior to completing obturation of the root canal.

- Seal the perforated site - this has been explained above.